One of the few television shows I watch religiously is Air Disasters. In the US it currently airs on the Smithsonian Channel and many episodes are available on YouTube. Many if not most of the episodes were produced in Canada, where it goes by the name of Mayday.

I don’t watch it out of morbid curiosity. Indeed, my favorite episodes are those where everyone, or at least some individuals, survive the accident. I watch Air Disasters because they are fantastic lessons in causality—almost every airplane crash is a concatenation of unusual circumstances. And because they offer fantastic insights on human performance under stress and human error.

Almost every accident contains an element of human error—not necessarily pilot error but nevertheless some type of human miscue caused by stress, exhaustion, unfortunate personal characteristics, or a poorly engineered process or system. The aviation industry to its great credit—spurred on by the usually stout oversight and regulation provided by government agencies responsible for aviation—has continuously revised its practices in light of the many lessons learned. As a result, airlines around the world have implemented strict rules governing the work and rest patterns of pilots and the interpersonal dynamics of cockpit crews.

The Intelligence Community could learn a lot about the performance of their workforce from the aviation industry. Indeed, watching the documentaries has led me to “appreciate” the considerable flaws of the IC’s work assumptions and practices. As the aviation industry has learned over the last 100 years, humans perform much better when they are positioned for success. So here are some lessons and concepts from the aviation industry that the IC should pay attention to. These are in fact relevant for anyone involved in difficult and/or risky work that must be reliably performed at a consistent high level.

- The Startle Factor. Almost all flights are routine. But often when something goes wrong it starts with a surprise—something happens to the plane or during the flight that the pilots had never previously experienced. The Startle Factor refers to how the human body and brain respond to such a surprise. Your heart races, your palms sweat, and your rational brain slows down. Instincts—for good or bad—may take over. Boeing had made an assumption with the 737 MAX advanced aviation system that the average pilot crew would only need a few seconds to realize when the system was malfunctioning and turn it off. But in the two crashes that grounded the 737 MAX, the crews were startled by the unexpected performance of the plane, their responses were delayed or incorrect, and hundreds lost their lives.

Intelligence officers can often find themselves in surprising predicaments. Does the IC take the startle factor into account when estimating the risk of certain operations? Even in the admittedly less dangerous work of the intelligence analyst, officers can be startled by new, unexpected information, leading them to misinterpret or ignore it.

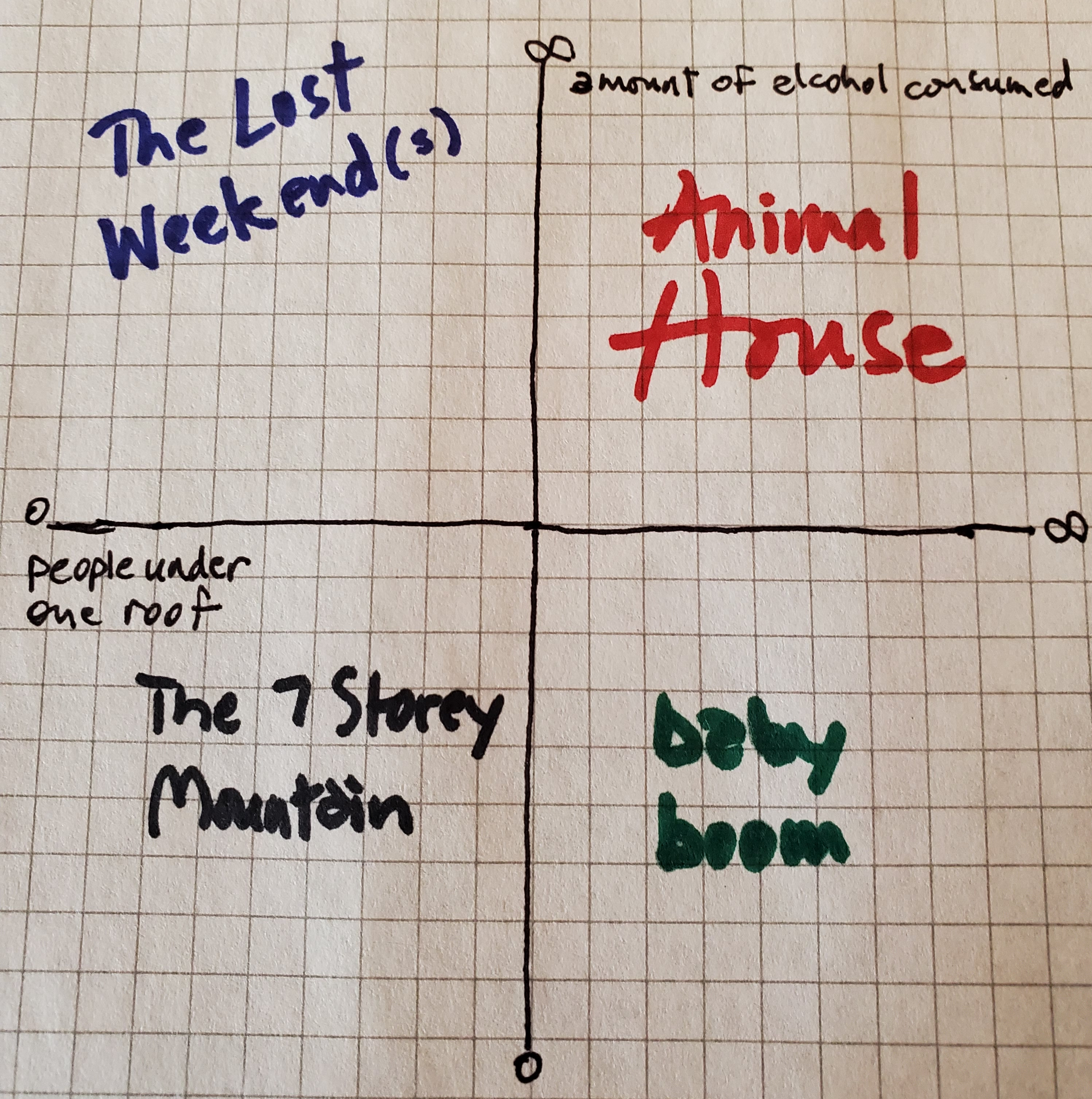

- The Importance of Sleep and Good Rest. Commercial airlines have strict rules about how many hours flight crews can work before they must rest. I imagine most of us have experienced a flight being cancelled because the crew has “timed out.” These rules reflect hard lessons learned about how poor rest and lack of sleep can degrade the cognitive performance and judgment of pilots. Every time I watch an episode where crew exhaustion was a factor, I think about how my old agency CIA ran task forces during crises. !2-hour shifts were common. I remember during the first Iraq war having to work 6 12-hour shifts per week. The aviation industry learned long ago that “people just have to tough it out” is not a useful strategy. IC agencies need to rethink the protocols associated with working during periods of crisis.

- Hierarchy Can Kill You. Traditionally the captain and the first officer in commercial aviation were in a command and obey-orders relationship. But captains are not infallible and there are several fatal accidents that could have been avoided if the first officer had been listened to. Oftentimes the captain would have had a hard time “hearing” the other view because the first officer actually never verbalized his concern. The respect for hierarchy was so paralyzing that first officers have deferred to wrongheaded captains even when it led to certain death. These types of accidents became so concerning for the aviation industry that airlines instituted mandatory crew resource management procedures that emphasize the importance of collaboration and teamwork in the cockpit.

When I started at CIA, it seemed to me that many of the most legendary leaders celebrated in agency lore were known for their authoritarian styles. Ugh! Strong leaders did not second guess themselves, always knew exactly what to do, and never tolerated backtalk. Somehow, we managed to do good things despite a flawed leadership tradition, and I’m happy to report that the agency’s leadership approach evolved while I was there. But there is still much more that could be done to improve our “crew resource management.” - Assholes Can Kill You. One of the most compelling and tragic airplane disasters is the story of Northwest Airlinks Flight 4719, which crashed in Minnesota in 1993 killing 18 people. In this crash, the captain was known to have a temper, often lashing out at airline employees, and belittling and intimidating his first officers. The investigators surmised that the first officer, who had been mocked throughout the flight, did not speak up to correct the captain about his too-steep descent. Toxic leaders are so harmful and intimidating that a person can choose death rather than confrontation.

- Even the Smartest Person in the Room Can Screw Up. Korean Airlines Flight 007 was shot down in 1983 after it strayed over Soviet airspace in the north Pacific Ocean. I was at CIA at the time, and I remember how incredulous we were and how scary the incident was during a period of heightened Cold War tensions. The actual cause of the accident was a mystery for more than ten years because the black boxes were not made available to investigators until 1992; the Soviets had recovered them and kept them locked away. When the flight data and voice recordings were analyzed, investigators concluded the veteran crew failed to correctly set the plane’s navigation system, leading the 747 to drift north of its flight plan and into Soviet territory. Navigational and communication issues occurred during the flight that should have alerted the crew to their error, but they apparently didn’t pay attention. The captain was a respected and experienced veteran. And he made a fatal mistake.

Expertise-driven organizations have to appreciate that expertise carries its own blinders and is not foolproof. Long and tedious routine—such as what occurs during a long flight–can also numb the intellect of even the smartest individual. - Checklists are Useful. One way to guard against the various blind spots of expertise and the inevitability of mental errors is to incorporate mandatory checklists into flight procedures. Too many airplane accidents have been caused by a cockpit crew overlooking or forgetting an essential step for flight, such as setting the flaps. When something goes wrong with a plane, crews consult extensive checklists although until recently they were printed on paper resulting in an increasingly frantic crew member paging through a binder trying to find the right section. (Luckily these are automated on newer planes)

When I was still at CIA I would imagine what an analysts’ checklist would look like. Perhaps even a “Turbo Tax’ application that would make sure the analysts considered all the wrinkles when producing an analytic product. I thought we could come up with a workable model, although it did worry me that, in an unintended consequence, analysts might react by behaving more like automatons than thinking human beings. With the arrival of ChatGPT and other artificial intelligence engines, my idea has perhaps been overtaken by events. - Distraction. Even the most competent cockpit crews can make egregious mistakes when they are distracted. Humans just aren’t that good at dealing with multiple tasks. A classic example is Eastern Airlines 401, which crashed in the Florida Everglades in 1972 when the pilots, trying to determine if their landing gear was properly down, failed to notice they had disengaged the autopilot and were rapidly losing altitude.

Many organizations, not just the Intelligence Community, have the habit of piling additional responsibilities onto teams without taking any away. This piece of advice was popular when I was at CIA: if you want something done, ask a busy person to do it. - Human/Technology Interaction. Technological advances have made commercial aviation the safest way to travel. And yet, as the Boeing 737 MAX crashes show, technologies that make ill-informed assumptions about how humans will react in unusual circumstances can create more and deadlier accidents. As planes become more advanced, the possibility of misjudging human interaction with technology grows. Another dynamic is that growing cockpit automation can lead pilots to lose touch with their ”analog” flying skills. Some airlines have lowered the requirements for flying experience to address the pilot shortage, reasoning in part that advanced cockpit automation now handles most piloting duties.

These are dangerous trends. There’s no doubt in my mind that advanced technologies will continue to replace human labor in many scenarios, including some of the more difficult tasks that humans perform. But as this process unfolds, we have to be clear about how reliance on technology can dull human talent and senses to the point that we become incapable of dealing with the unexpected concatenation of circumstances on which the software was never trained. - Who’s Accountable? The final lesson I’ve learned is how to think about “accountability” in complex systems. As airline crash investigators know, many airplane accidents involve a chain of unlikely events, any one of which would rarely occur. A supervisor decides to pitch in and help his overworked maintenance team by removing a set of screws. The maintenance team isn’t able to finish the job but don’t know to replace the screws. Nevertheless, the plane makes many safe landings and takeoffs until a pilot decides to make an unusually fast descent. The pilot and all the passengers die.

Who exactly is accountable here? Is it the supervisor who tried to be helpful? Or the airline management that under-resourced its maintenance operations? Or the pilot? In many organizations, holding someone “accountable” is the signature move of “strong leaders”. But what often happens is that some unfortunate individual is held to blame for what was a systemic failure of an organization—often driven by complacency, expediency, and/or greed.

The aviation industry’s motivation to eliminate airplane crashes has created a strong safety and lessons-learned culture, but as the experience with the 737 MAX shows, positive outcomes depend upon persistent vigilance. The Intelligence Community has long claimed that what it does is unique and that lessons learned from other industries are not always applicable. But the human being remains the same: we don’t employ unicorns but rather just normal folk, who can make mistakes, who need sleep, and who perform best when they’re positioned for success.

The

The